Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Characteristic of her style, the list repeats words and phrases for emphasis.

Evicted, Berlin writes of her home in Berkeley, California.OfOakland, too: Evicted, evicted.

In her fiction, Berlins repetitions feel weightless, incantatory.

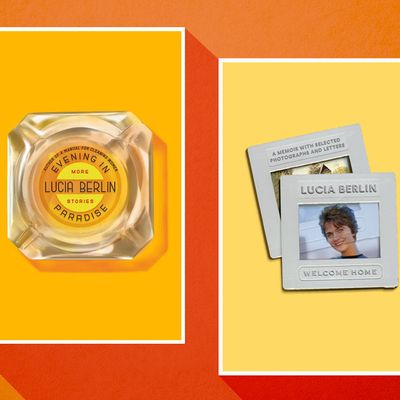

But in this document included in her memoirWelcome Home, out this week they have a different effect.

Rather than her awe, we feel her exhaustion, the drudgery of her repetitive chores.

We feel, also, how fed up she is with her state of existential homelessness.

When, and where, will she finally feel at ease?

Why does her writing resonate so strongly today and not while she was alive?

But Berlin seemed almost to transcribe her memories, over and over, into quick, lyrical scenes.

As with Heti or Knausgaard, theres a sense of urgency and compulsion in Berlins stories.

The current popularity of auto-fiction, along with the impulse to recover womens narratives, might explain Berlins resurgence.

Berlin lived that way too, except that she also wrote.

Because of her fathers work, Berlin spent much of her childhood moving from house to house.

It was around this time that she started writing letters.

At 11, she wrote to her father, and already her voice was both playful and direct.

Of a trip to the theater, she wrote, I couldnt go and besides I didnt want to.

Berlin didnt inherit her fathers sentimental style; her words are tactile, specific.

Her letters mention many such provisional living spaces.

But it wasnt just her life as a transient that made her long for the solidity of a home.

It was her tumultuous family, too.

Some of these misadventures were adapted into violent stories, like Dr. H.A.

A few months after the blowup, Berlin married a sculptor namedPaul Suttman.

I held the hot part of the cup and gave him the handle, she writes in her memoir.

I ironed his jockey shorts so they would be warm.

It was as if Berlin no longer saw in herself the person she used to be.

With Race, Berlin began writing more seriously.

Ive never known a family, she wrote, calling the possibility both nice and terrifying.

Regardless, she concluded, I suddenly have 100s of things to write.

Around this time, Berlin mailed some of her stories to Kerouac.

Both wrote about vagrancy, having lived in cars, trains, and buses.

But while Kerouacs writing sprawls, Berlins is more solid; it hammers.

Verbs and nouns are granted whole sentences.

Of her home in Idaho, she writes, simply, Creaks.

Or, scrapings and hisses and thuds.

Of Kentucky: Fireflies.

There are no mixed metaphors about roman candles popping like spiders.

Theres just the word itself, ringing or buzzing.

Kerouac, who felt his childhood was tarnished by order, tried to escape it.

Most of her stories are short and efficient, and most of her characters are remarkably still.

They look out of windows.

They sit on the roof.

They bicker over drinks.

These characters, plucked from Berlins adult life, didnt go on adventures.

Instead, no matter where they traveled, the monotony that so often accompanied a womans life invariably followed.

(Poor people wait a lot, she writes.)

The narrator is tasked with finding her clients missing puzzle piece.

When she does, she cries out, and the two women rejoice.

Its a neat encapsulation of Berlins work, and of her life.

Theres an ambivalence about domestic spaces, which are stifling but also a comfort.

And, amid so much chaos, something as small as a found puzzle piece is cathartic.

Theres delight, relief.

For a moment, theres order.